I’ve been wrestling with the concept of “having it all” for more than twenty years.

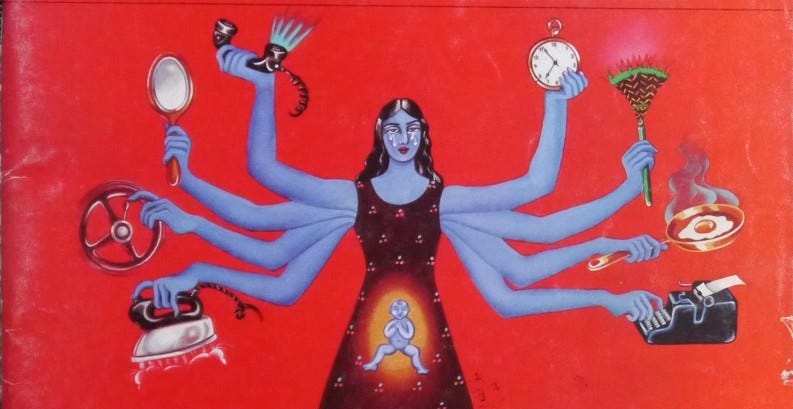

In my twenties and early thirties, that obsession was fueled by frustration: the way career and motherhood were framed as mutually exclusive, as though to choose one was to automatically negate the other. In more recent years, my fascination has shifted to the ideological function of the phrase itself — how it polices women’s ambition and makes our desire to live full, three-dimensional lives seem greedy, excessive, and impossible.

These questions run through two projects I’ve been quietly working on over the last couple of years: a documentary podcast tracing the history of the phrase from the 1970s through the 2020s, and a memoir-manifesto about what it means to build a full life as a woman who chooses to be a mother.

Why this obsession? Because we’ve gotten “having it all” all wrong.

Ask most women my age, and they’ll say the problem is that we were falsely told we could have it all, when the reality is that we can’t. That having it all was always a false promise: exhausting, unattainable, a relic of corporate white feminism. But that story doesn’t hold up. Look closely at the past fifty years (and I have!), and you’ll find that women were almost never told they could have it all. The phrase has mostly been used to describe what we can’t have.

The point of “having it all” has never been to impose an impossible expectation. It has been to make women’s very ordinary desires — for ambition, family, creativity, love, rest — appear unreasonable, while narrowing the idea of a “full life” for women to just two forms of service: service to an employer, and service to a family.

When the idea first surfaced in the late 1960s and 1970s, it wasn’t primarily about mothers balancing jobs and kids. It was about women carving out lives on their own terms: single women, childfree women, women who chose to marry and have children, but who rejected being defined solely as wife and mother. Only in the 1980s did the phrase harden into the caricature we know today — the harried working mother who wants too much, to the detriment of her children, her boss, and herself.

It’s easy to think of “having it all” as a cultural relic, but the phrase — and the ideas behind it — are still everywhere. Sometimes it’s invoked to celebrate conservative women who we’re told have cracked the code on doing it all. Sometimes it’s rejected outright by younger women who look at the lives of their millennial elders: that’s not what we want. Media stories cycle endlessly through the refrain “no one can have it all,” as if it were a revelation, when in truth it has been the dominant story for decades.

And all of this is happening at a moment when conservative gender roles are being glamorized again: glossy “tradwife” aesthetics on social media, women celebrated for domestic service while men are celebrated for public life, and conservative influencers calling for “less burnout, more babies.”

Which brings me to this new project.

Having It All will be the space where I publish essays on feminism’s unfinished revolution and the fight for a full life. I’ll explore:

the history of the phrase and the ways it has been used to discipline women’s desires;

the real factors that constrain women’s lives, whether they are single, partnered, mothers or not;

the political and cultural backlash that seeks to roll back gains and re-domesticate women; and

how we might reclaim the phrase for what it was originally meant to signify: the right to wholeness, freedom, and full humanity.

About me:

I’m Rachel Hills. I’ve spent the past two decades circling the same set of questions: how women’s lives are imagined, celebrated, or curtailed by culture; how ambition and family are pitted against each other; and what it really takes to live fully as ourselves.

I’ve written on these themes for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Cut, and Cosmopolitan, among many others, and I explored them in depth in my first book, The Sex Myth, which challenged the hidden rules around sex and identity and went on to spark global conversations.

This Substack is where I’ll be thinking in public — writing essays that wrestle with feminism’s unfinished revolution and the fight for a full life. I live in Brooklyn with my husband and our son, and like most women I know, I’m working out in real time what it means to “have it all.”

If you’re interested in feminism’s unfinished revolution, in how gender equality is won and lost, and in the fight for full lives for women, I’d be delighted if you’d join me here.

took me a moment to get to reading this piece, so i'm so glad Jill's newsletter recommended it again. Such great writing.